Harvey’s Nugget

By Mike Osborn

In the pages of Australia’s history, tales of fortune and misfortune abound, with the former a source of nourishment for the “gold fever” in all of us. Luckily though, even the worst of our misfortunes seem to fade with time. As precious a thing as gold most certainly is, it can be a cruel addiction, bringing out the worst in human nature between even the closest of friends. The story of “Harvey’s Nugget” is a tale of cruelty indeed, one that I won’t forget easily and one that shows that “gold fever” is as real an affliction as any disease can be. Harvey’s position in life is an envious one. As a staff writer for the American National Geographic magazine, he travels the world to far flung and exotic locations, wielding an expense account that provides him with a comfortable existence, free of the budgetary constraints that might restrict the average traveller to a limited time frame and an overloaded credit card. Determination, hard work, months at a time away from a growing family and an ability worthy of his post, had earned him that position. “Coin shooting” as he calls it, is Harvey’s one and only selfindulging passion, a pastime relegated to the limited free time he has to himself in his home town of Washington DC. Combing the parks, bus stops, playing fields and public areas of a major capital city with a metal detector may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but for Harvey, it satisfied his prospecting instincts and kept him in touch with his ambition of one day sifting through the goldfields of Australia, looking for the “fist-sized nuggets” he had heard, read, thought and dreamt about. His trusty Fisher Gold Bug detector was antiquated and somewhat battered by the time he came to realise his dream.

The saga of “Harvey’s Nugget” had an innocent enough beginning. The editors at the National Geographic offices in Washington had decided to feature Western Australia’s northwest in an issue of the magazine. The process of selecting writers and photographers had come and gone with Harvey accepting the writer’s assignment with a delight that must have bemused his superiors. For Harvey, it was the start of an adventure that would fulfil a decades-long ambition – prospecting for gold in the Australian goldfields. He had packed his trusty Gold Bug and a pile of research material and boarded the plane for the long flight to Darwin (before travelling to the starting point of his journey at Kununurra in WA’s Kimberley). I had never met Harvey before and I was to be his guide and companion for the two months that were allocated to him to travel the north-west and put together the information required for the feature.

National Geographic feature writer, Harvey Arden

My credentials didn’t include a successful career as a gold prospector but I knew enough to try and dampen some of Harvey’s expectations of abundant and easily-detected nuggets in the Kimberley, Pilbara, Gascoyne and Murchison regions of WA. I had spent a year or so at Kalgoorlie, the heart of WA gold-bearing country, and while I had dabbled with detecting, the greatest reward for my efforts was the well-rusted workings of an old leveraction carbine! Harvey also categorised his prospecting expertise below that of a rank amateur so luck was going to have to play a major role if any trace of gold was to cross our paths! It was at Old Halls Creek in the Kimberley where Harvey and I made our first foray into a “goldfield”. It was very much a touristoriented approach, purchasing a “prospector’s licence” to work a patch set aside by the leaseholder to accommodate the wanderings of would-be fortune seekers on his ground. We were assured that gold was to be found if we worked hard and long enough! As luck would have it, I found a rusted lever from a carbine to match the one I’d found at Kalgoorlie but that was all that came to light and we moved on. Changing from our allocated patch proved to be a poor decision. “Trespassers will be shot” read the hand-painted sign at the entrance to the next track. We assumed it wasn’t a joke and decided to try our luck further south in the more expansive fields of the Murchison.

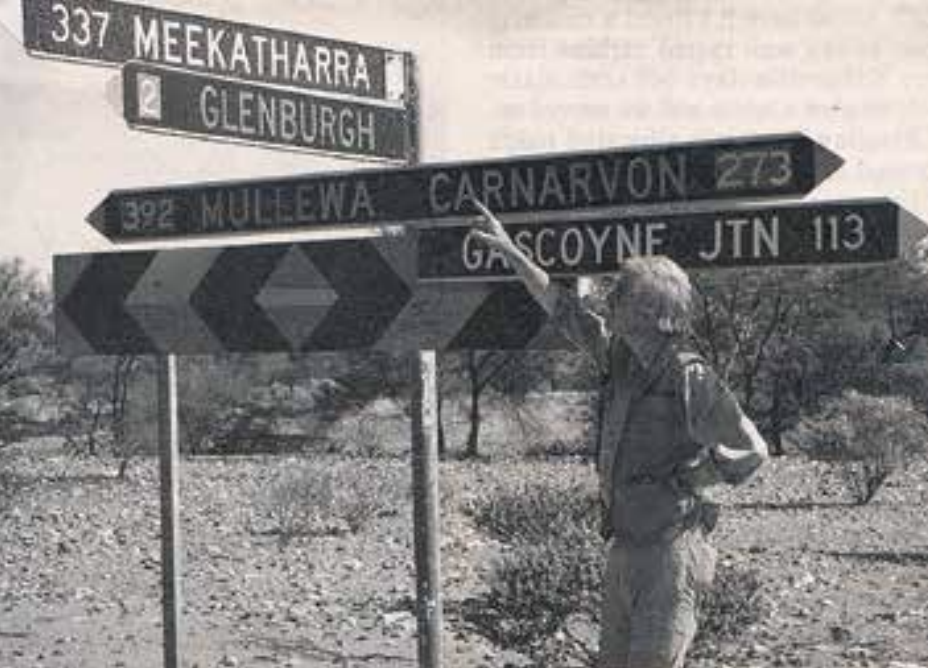

Meekatharra was to be the setting for our next prospecting escapade. Harvey was determined to stay on the less troublesome side of the law as it applied to detector-wielding gold seekers such as us. For one thing, the signs that dotted the pock-marked landscape gave us ample warning of the consequences of poking about on a lease without the appropriate invitation. The second and perhaps more important consideration was that if Harvey was to write about our escapades in any detail, he would need to show that he had kept within the constraints of the law. This meant finding a “friendly” prospector; someone who would be willing to share his precious lease with a couple of “out of towners” for a day or two. The responses my approach received were interesting to say the least and needless to say, none were positive.

I tried a different tack and sought advice from the local Department of Mines. The staff were friendly and extremely helpful but of course there were no available leases up for grabs, at least not anywhere within coo-ee of anything resembling gold country. It seems that companies had blanketed just about any area of worth, and a few extra just for good measure. The last resort was an approach to one of the large company operations.

Harvey Arden looking for directions to his nugget

My introductory call to one of the largest privately owned mines was received politely, with understanding and best of all, with an invitation to visit the mine office to discuss the matter. I have no doubt Harvey’s connection with National Geographic drew the invitation. We were treated to coffee and a tour of the crushing plant and workings. I was impressed – Haulpak mining trucks, semi-trailers, 4WDs and machinery were everywhere. This was indeed a big operation. It was hard to imagine that it was all owned by one man. I had broached the subject of detecting on the mine lease earlier that day during the introductory phone call, and didn’t strike any opposition. “Would you mind?” I asked again, just to make sure. It seems that we were the first to ever ask to do such a thing and were told tales of those who hadn’t had the courtesy to do so, even some of the mine staff, it seems, couldn’t resist the temptation of working the ground after hours. Permission was granted and we were pointed in the direction of the main mine site several kilometres away with instructions to contact the foreman of the site. As we exited the airconditioned offices, the lady who had been so helpful and accommodating when I had first contacted the company, said: “Of course, if you find anything over an ounce you will have to let us know!” Harvey and I took it as a joke and to this day I’m sure it was meant as one.

Excitement and anticipation were literally oozing from Harvey by this stage. The mine foreman was a little surprised that we had been given approval but was friendly and accommodating. He took us to a small hillock almost totally surrounded by a dry salt lake, and this was to be our allocated patch. Before the foreman left, he gave us a little history of the hillock, saying that this precise location was the site of many of the largest and most prolific nuggets that the lease had produced. I passed on the “if you find anything over an ounce” joke and he laughed. The shine from my rising interest in possibly finding a speck of gold was sullied with his parting comment “The ground has been worked real hard; give it a go though, you might get lucky.” I don’t know why but I had naively thought that we would end up in some little out of the way spot, instead we were within one hundred metres of Haulpaks dumping overburden onto a mound that was heading in our direction. Harvey was too excited to worry about much and was already slipping the earphones into place. After 20 minutes or so of probing the ground, Harvey walked over to our parked Landcruiser muttering something about changing the batteries in his detector. A few minutes later and with a newly-charged machine, he was back at it, swinging to and fro, occasionally chipping with his rock pick at nothing more significant than the pull-tops of beer cans or chips of metal from the bulldozer tracks.

We were no further than 20 metres from our vehicle when Harvey walked over to me and queried “What do you think this is Mike?” The tremble in his voice belied his expectations. We both knew that it was gold! A nugget the size of an egg! Dirty and dusty maybe but it was gold. Just a few minutes earlier I was thinking to myself that perhaps Harvey’s trusty Fisher was about as useful as an ashtray on a motorbike but at that moment, I worshipped it as a marvel of microchips and plastic! The remainder of the afternoon flashed past and nightfall saw us back at the comfortable lodgings of a Meekatharra motel. There we were, two grown men acting like hyperactive kids at a birthday party. That one piece of gold triggered a euphoria in Harvey that was contagious. The smile could barely fit across his face. The nugget was caressed, fondled, washed in the bathroom sink, examined with a magnifier, names were thought up for it and the circumstances of its discovery were recounted a dozen times over. Neither of us had any idea of the weight or value of the nugget. It contained a small amount of rose-coloured quartz but in essence it was all gold. At dinner that night in the motel dining room, the temptation to weigh it became too much to bear. We must have looked a strange sight to the chef and kitchen staff as Harvey gently released the lump of rock onto the scales alongside the rack of spices. One hundred grams! Back in the motel room we began to return to an acceptable level of behaviour for adults and the significance of Harvey’s find began to set in.

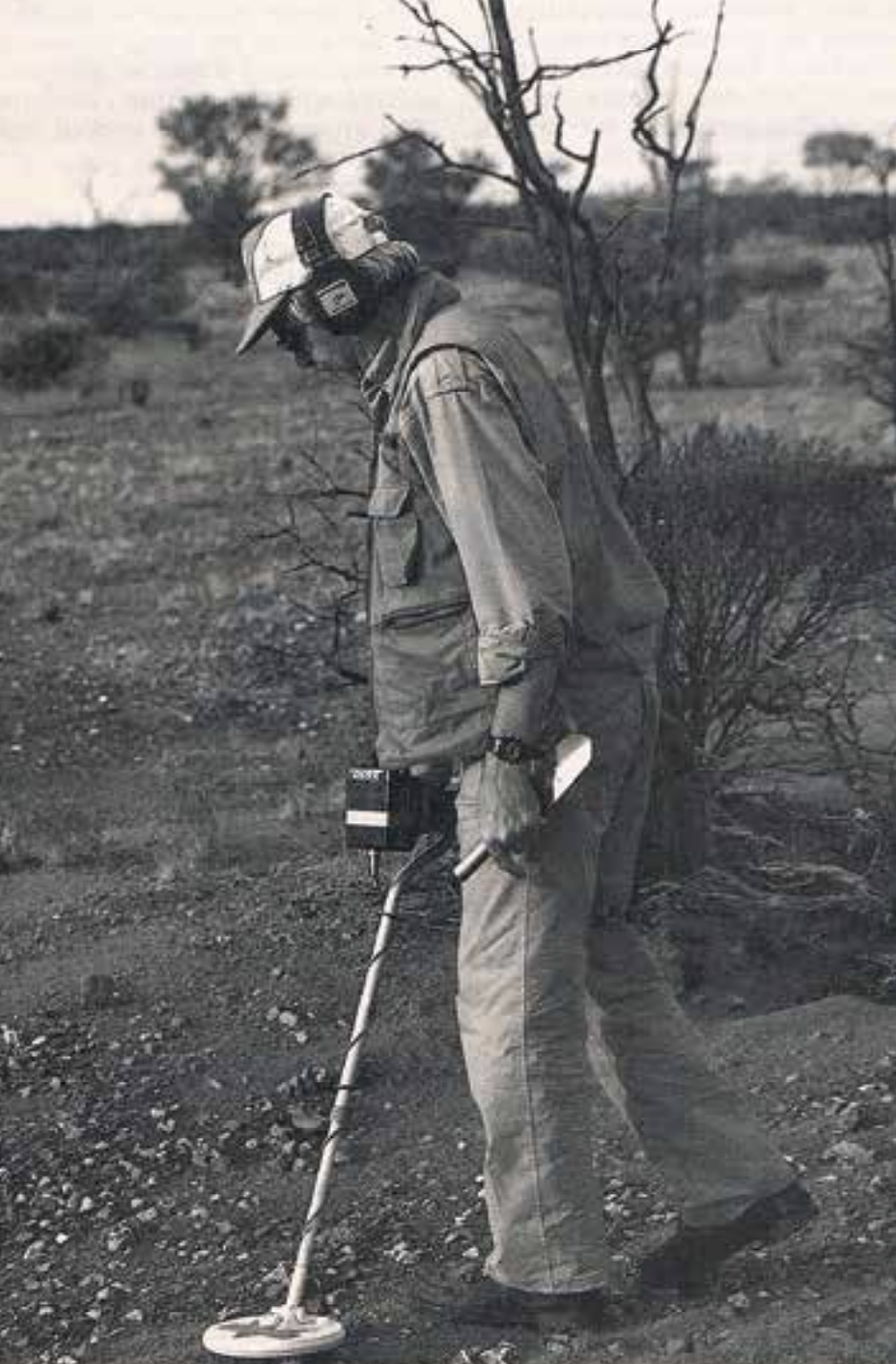

Harvey finally realized his ambition to go gold prospecting in the goldfields of Australia

The implication of those words “of course if you find anything over an ounce you will have to let us know” began to play on Harvey’s mind. I helped him wrestle with his conscience for an hour or so. Should we tell the mine staff? What will be their reaction? Worst of all, will they want to take possession of the nugget? To be truthful, the thought of keeping the gold overrode Harvey’s honesty for a short while. The fact that we had been treated more than fairly by the mine management, the usefulness of the nugget for Harvey’s article and simply being able to tell the tale of the nugget to friends without the nagging feeling that a touch of dishonesty can bring, saw us arrive at the same conclusion. First thing the next morning I would phone the company to announce the discovery of yet another memorable nugget from that small hillock. We discussed the pros and cons of this course of action late into the night and finally slept, comfortable in the thought that at least we were doing the “right” thing. Harvey’s fears of having to hand over the nugget were allayed as I hung up the phone. “Great,” said the girl from the mine office. “Bring it in and I’ll get it cleaned in acid for you. We have a box or two around here to put it in if you want.” But the next day in the mine office, the atmosphere was no longer one of smiles all round. The girl who had been so friendly the day before, walked out of the plush office and returned a short time later, bringing with her a geologist. You could have sliced the air with a knife. I was feeling uncomfortable to say the least and the expression on the face of our now, not so friendly, acquaintance was as good an antidote as could be found anywhere for the gold fever that had gripped Harvey and me for the last 18 hours.

It seems that “Harvey’s Nugget” had created a dilemma for the mine administration and an embarrassment for the geologist. Clearly the administration was in damage control mode and we discovered why after poring over maps and pinpointing the location of Harvey’s find. To me, a 100-gram nugget was the find of a lifetime. Even if it wasn’t me that picked it up, just to be a part of it was a thrill. To an operation such as the show we were at, I daresay the value of that nugget at the time would not exceed the tea break costs for one day. I was struggling to understand the problem that confronted the nervous and embarrassed duo standing in front of me. The nugget rested on a table between us, (us and them that is), with ownership open for debate. Awkwardly, the story unfolded. To start with, no one at all considered it likely that Harvey would realise anything other than dusty shoes and drained detector batteries in our allotted patch. The geologist was somewhat red-faced as the mound of overburden and tailings heading in the direction of “Harvey’s Hillock” (we took the liberty of renaming the site) was due to cover it in a day or so. Obviously, the operational plans for that area would need closer scrutiny. Finally, the main stumbling block between the nugget and Harvey’s possession of it was the owner of the mine. As it turned out, the owner was overseas at the time of our visit and although our friendly and accommodating girl had sufficient authority to offer us permission to do what we had done, a decision on the final resting place of “Harvey’s Nugget” would need to be made by the mine proprietor. A polite verbal and mental tug of war over the temporary custody of the nugget took place between our girl and Harvey, resulting in promises of its safe keeping until the mine owner could be contacted. An assurance was given that under no circumstances would the nugget be crushed. It was planned for a studio photograph of the nugget to be taken for the magazine article.

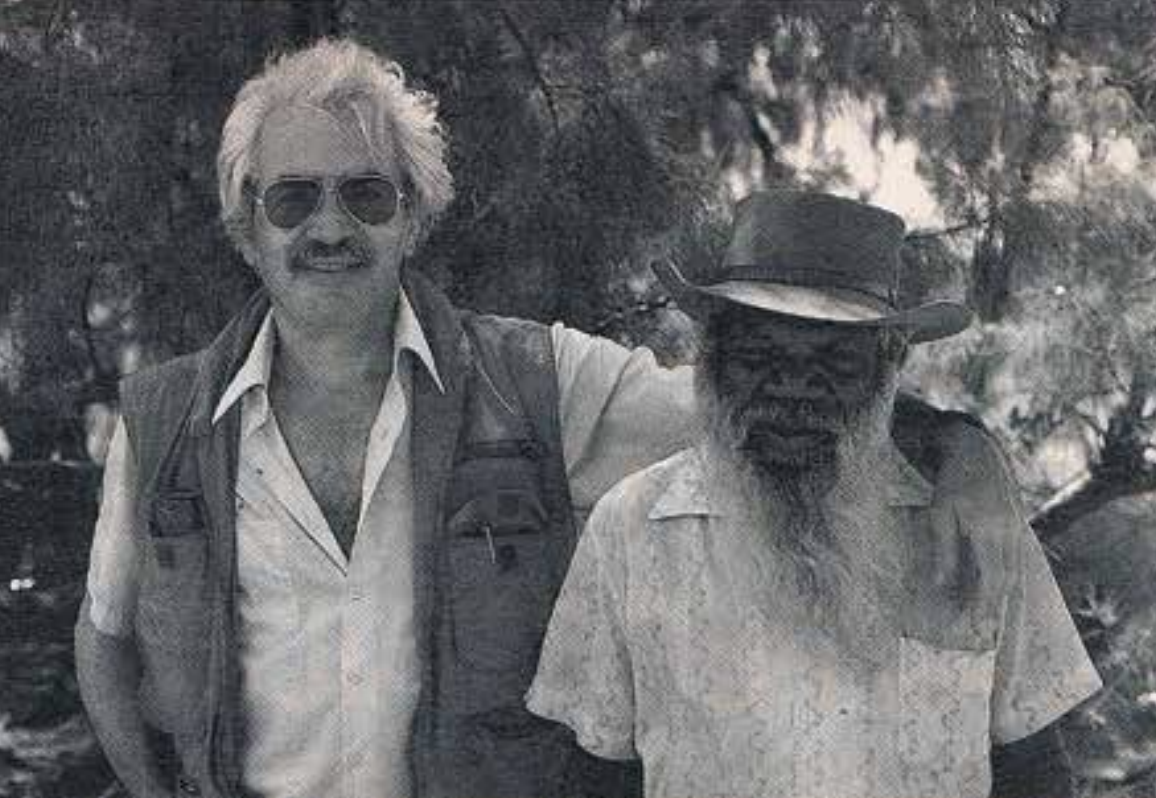

Enlisting the help of one of the locals near Halls Creek in the Kimberley, where specking nuggets after the monsoon rains of the “wet” season can be done with a degree of success

A letter was penned to the owner explaining the situation exactly as it had occurred, apologising for the inconvenience and as a sincere gesture, Harvey offered to pay for the value of the nugget because for him, the nugget was the fulfilment of a lifelong ambition and he wasn’t about to let it get away. We left Meekatharra that day secure in the knowledge that even if all else failed, the proposed photograph would enable fond memories of that fulfilled ambition to be had. The following weeks saw us attending to the various other aspects of our task. My persistent telephone calls to the mine raised little response, with the offered explanations of “he is still overseas” doing little to bolster my assurances to Harvey that we Australians were a fair and just race. I mulled the situation over in my mind time and again and thought that even if the worst came to the worst, Harvey would still possess his nugget, albeit after having to part with the cash if need be. My last phone call to Meekatharra was from Darwin on the day of Harvey’s departure from Australia. “The nugget doesn’t exist anymore. We put it through the crusher,” was the cold and curt response. I walked into Harvey’s room not really knowing what to say. I had wanted for him to leave Australia with an impression of our country and its population that would be reflected in his article. Harvey obviously sensed my uneasiness before I spoke. I blurted out the news that signalled the demise of his dream. His reply reflected an attitude that mirrored his approach to life’s cruel blows: “Ah well, the real value of that nugget is in my heart and they can’t crush that.” We wandered down to the bar and toasted the end of the nugget with a beer. The brand? Swan Gold!

Editor’s Note: Harvey Arden worked as a senior writer for National Geographic magazine for 23 years and produced some of the magazine’s most memorable stories. He was also the editor, author and co-author of numerous books. He passed away on the 17th of November, 2018, at the age of 83.