November 2025 Issue Available At All Leading Newsagents!

Read the featured article from this month’s issue below

Northern Territory gold

by Bushranger

We’d had the good fortune of having found gold in each state we’d visited in the past few years – Queensland, New South Wales and “Mexico” (Victoria) – and now it was time to turn our attention to the Northern Territory. Like NSW, the NT didn’t make you purchase a licence to fossick for gold but there were limits on the quantities of gemstones and minerals, including gold, you could remove. In Victoria a Miner’s Right will set you back $24.20 but that is for 10 years. Only Queensland rips you off by charging either $8.50 for one month, $32.25 for six months or $54.30 for an individual for one year!

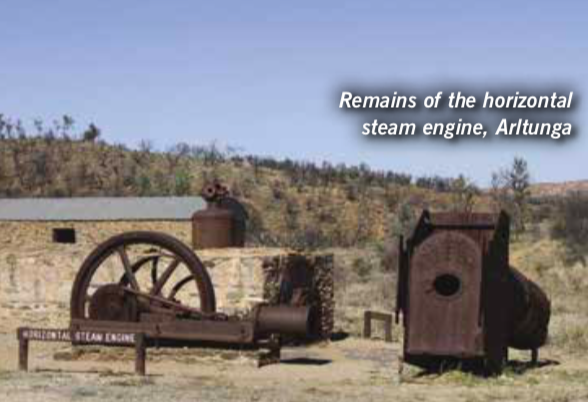

While exploring the East MacDonnell Ranges, we visited the long-deserted gold rush town Arltunga, about 110km east of Alice Springs. Arltunga was the first major European settlement in Central Australia and the town was named after a subgroup of the Arrente Aborigines who had been living in the area for thousands of years.

The author’s biggest helping of NT gold

The Arltunga Visitor Information Centre has an excellent display of historical photographs and objects, and plenty of information about the history of the area, including descriptions of the mining techniques that were used in this unforgiving desert environment. We prospected for one week on the Arltunga goldfield and found several large gold-quartz specimens, some jasper, and a few interesting copper-quartz specimens. In the late 1880’s, the explorer David Lindsay, trekked through the area and observed that there appeared to be “rubies” in the bed of the Hale River at a location which was subsequently named Ruby Gap. A few years later, it was found that these gemstones were in fact high-grade garnets, and not gemstone-quality rubies, which, back then, attracted excellent prices in London.

A gold-on-quartz specimen for the collection

We found several small gem-quality pink garnets at Ruby Gap and Glen Annie Gorge, and in some parts of the dry, sandy bed of the Hale River we found areas of relatively recent wash which contained thousands of tiny pink garnets glistening in the sunlight.

After much research, including talking to several long-time NT gold prospectors and cattlemen, we suspected that our best chance of detecting gold would likely be in an area which was claimed to be “the richest alluvial goldfield in the Northern Territory.”

Fortunately, we obtained permission to fossick on a one-million- acre cattle station while the owners were conducting aerial mustering operations. We felt honoured, as complete strangers, to be the sole recipients of such incredible kindness from this wonderful family.

Over the next 10 days we were the only authorised fossickers on this huge property, and we explored some stunning and harsh terrain. We covered a lot of ground on foot, walking up to 22km per day, and covering more than 100km in seven days, in hot, dusty and windy conditions. Most days I swung my Minelab SDC 2300 for up to seven hours per day, and downed up to eight litres of water per day to keep hydrated. Fortunately I had a spare protective skid- plate cover for my detector coil as the sharp, hard rocks gouged through the plastic cover within a week of use.

The super-heavy duty ‘Little Brother Digger’ pick I bought on eBay was excellent for breaking the hard ground I encountered on a daily basis, and a 10mm heavy-duty, hardened steel chain was just the ticket for drag-gridding the small patches I found. Loaded up with all my gear, which probably added about 20% to my body weight, I felt like a pack mule but the custom-made soft orthotic insoles in my Aussie-made Redback boots made the task of trekking a lot easier. As a result of the hard yards we put in, we found gold nuggets and/or gold-on- quartz specimens every day, mainly near “greenstone” outcrops and “floater” boulders. I also found two patches where we recovered multiple gold nuggets. We also found several fine specimens of agate and jasper.

I have now used my SDC2300 for a few thousand hours in the field and am very impressed by the performance of this “Fast Pulse Inductor”. I’ve also had the opportunity to provide feedback to its inventor, Dr Bruce Candy.

I recently purchased some enhancement accessories for the 2300, including an acoustic soundshell and a knuckle cover, and am currently considering the merits of Garnets from Ruby Gap buying an 11-inch Coiltek Gold Extreme coil for detecting gold at greater depths.

Technically, an 11-inch coil has a diameter which is about 35% longer, and a surface area about 90% larger than the standard Minelab 8-inch coil. Coiltek provided air-testing data (of a 20-cent coin) which suggested an increased “air” detection depth in the order of about 20% using the 11-inch coil compared with the 8-inch coil. So, in some instances, I might achieve an increased detection depth of five or six centimetres.

Explorer David Lindsay (1856- 1922). In 1885 and 1886 Lindsay surveyed the country between the overland telegraph line and the Queensland border, explored the MacDonnell Ranges, made a brief foray into the Simpson Desert, and spent six month in the country between Lake Nash and Powell’s Creek

It makes me wonder how many slightly deeper gold nuggets I passed my coil over without knowing they were there. My “wish-list” prospecting kit would also include the addition of a “discontinued” Minelab GPX4500, complemented by a Nugget Finder Evo 15-inch coil. I better talk to my Minister of Food, Fashion & Finance about such a worthy future investment!

Remembering the 2,000-ounce patch

by Bruce R. Legendre

When one thinks of big nuggets, monsters such as the Welcome Stranger, the Welcome, the Golden Eagle, and the more recent Hand of Faith all come to mind. Well, we never found a single nugget that came remotely close to any of the four I just mentioned, but my brother, Joe, and I were involved in a couple of patches that went better than 1,500 ounces all up. Not that we got to keep it all, but we were the ones who found the first nuggets in new country where no-one had looked before, or if they had, they’d missed it. I also prospected in two other areas in the Stirling Ranges just north of Leonora where two patches were found that went better than 700 ounces. One was the Royal Arthur found by the Leonora Aborigines in 1989, which turned into a real free-for-all with half the town out there and everybody getting good gold. Believe it or not, it was only 600 or 700 metres from a series of shafts and right in the guts of this new alluvial find was a small surface dig from the old days. The other patch was found close to Mount Fouracre. Peter Randles walked onto it and the exact number of ounces it produced was, well, let’s just say many hundreds.

That patch was situated right next to one of the major tracks in the area with workings to the south and east. The area had been hammered by everyone from Leonora, the local Aborigines, and tourists from every state, but when I visited Peter I had to laugh when he told me he had twigged two beautiful quartz specimens for 30 ounces which had been hiding underneath low hanging mulga branches, the kind that hug the ground. It was the old story of everyone being too lazy to move a few tree limbs that were in the way.

The old extensive alluvial patches where the old timers blew hectares and hectares of loam, like Lake Darlot, Duketon, and Wilsons’ Patch, produced tens of thousands of ounces for the metal detector operators who had been working them since 1977, when it all started with the Garrett Deepseeker. But the best patch, without a doubt, was David John’s prospect in the Goanna Patch. It went 2,000 ounces before David flogged it for a quarter of a million and headed off into the sunrise to the eastern opal fields. My brother, Big Royce, and I were prospecting north of David’s ground back in 1985 and 1986 and we called in to say hello every month or so on our way out of town, having made the run to replenish supplies.

Copies of David John’s book, Bloody Gold, which details the difficulties he faced in winning gold from the Goanna Patch, are hard to come by these days

They were exciting times for David. The gold was coming in daily and it was very good gold. David always enjoyed a bit of company in those days and was celebrating his good fortune on a daily basis: a slab of beer and a bottle of rum together with a few hundred ounces of metal to admire, made for a very festive atmosphere, particularly when we were coming in on the bones of our arse not having found anything in weeks and weeks.

How the whole show came together was that David had given up commercial fishing in South Australia and came out to Leonora as a new chum, with limited assets, an old milk delivery van, a Garrett A2B, and the ability to find just enough gold to keep body and soul together. He’d pegged an SPL (Special Prospectors License) on a mineral claim that was held by a large company as one of many that carpeted the entire area. They did little or no work, content to sit on the ground in a speculative fashion hoping that one day something would occur that would enable them to make money. This modus operandi actually worked if you could hold onto ground long enough and were prepared to fictionalise your annual work reports.

Well, the warden in Leonora’s monthly court granted David the SPL which was no mean feat I can assure you, having attempted the same thing myself with no success. If the opposition showed up maintaining that they were planning an exploration project in the area that you’d pegged, well, you were up the proverbial creek. David had done his homework and was truly prepared to work the ground.

He put a few dry blow shots through a small sampling machine that ran off the battery of a motorcar, and was powered by a windscreen wiper motor. He’d gotten colours of similar texture and size on both sides of a creek and figured that the middle ground between the two must be the source. So he put his entire bankroll – the grand total of 1.5 ounces of gold – into renting a backhoe for half a day. That was it. Half a day to produce the goods or the fat lady had sung.

The backhoe operator came down from Leinster and put in a costean through the creek where David reckoned it might be. Well, to cut a long story short, there ended up being more than 200 ounces in the mullock heaps alone! It was more than enough to kick-start any alluvial operation. David went and bought himself a Cat D7, a compressor, a motor grader, a rock drill, gelignite, another caravan and ute, and heaps of good tucker and refreshments.

He then systematically scraped an area of several hectares over the next couple of years, working some days, celebrating others. He kept all the metal somewhere in his camp which was common knowledge in the goldfields, but I don’t think anyone was game to take him on as he had a reputation of being a bit eccentric and heavily armed – a reputation that I can assure you, was on the money.

David’s 2,000 ounces made him the king of the Eastern goldfields. I saw him every now and then in Leonora after he’d returned from the opal fields. He’d decided to have another crack at gold. Like all of us, he was broader around the waist and his hard drinking days were over.

Today the goldfields need fresh blood. All you need is a reliable detector, a reasonable vehicle and patience, patience, patience. Once you read about the boom, it’s too late. But it can never be too early if you’ve got very little to lose for starters. So, if you’re broke, depressed, have had a gutful of being a citizen or all of the above – have you tried being a prospector?

Life and death in the Queensland gold escort

With the discovery of gold in Australia in the 1850s, there came a time when the police force had to perform extra duties in and around the gold mining towns. As well as making arrests, and serving warrants and summons, one of their main responsibilities was gold escort duties. The first ever gold escort departed Mount

Alexander near Castlemaine, Victoria, on 5th March, 1852, carrying 5,199 ounces of gold and arrived in Adelaide two weeks later. Eventually, 18 trips were made between 1852 and 1853 transporting 328,502 ounces of gold. The Victorian- goldfields to Adelaide route was notable for the distance and amount of gold carried – almost a quarter of all gold, 1,520,578 ounces, transported within Victoria during the gold rush years from 1851 to 1865.

Queensland separated from NSW in 1859 and between 1861 and 1867 there were a number of gold discoveries at Clermont, Cloncurry, Cape River, Nanango, Gympie and Kilkivan. Because of the vast distances that had to be travelled in order to deliver the gold to the banks, and because Queensland could no longer draw on police manpower from NSW, the gold escort was formed in Queensland in 1864.

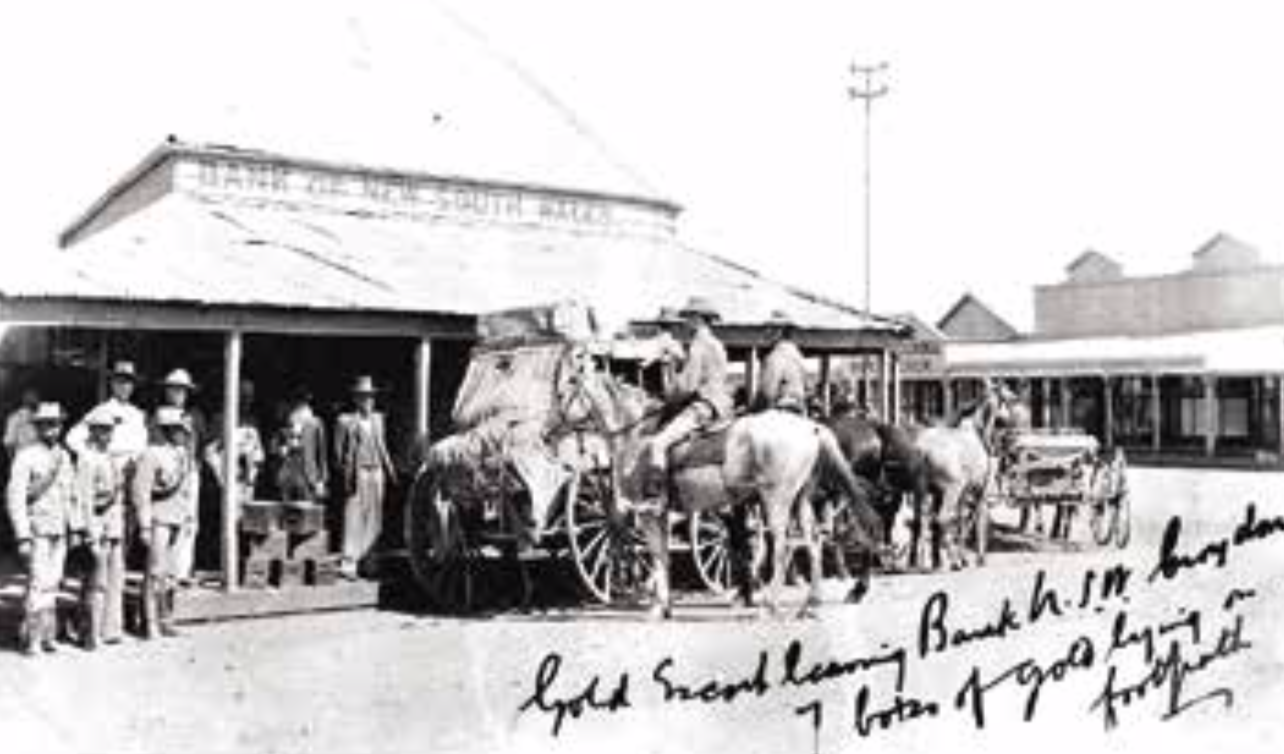

Gold escort group photographed at Normanton, c.1895

Because of the dangers involved, the pay was doubled for any policeman while he was actually escorting the gold to its destination. The ever-present danger of robbery, accidents, and attacks from Aborigines were part and parcel of life for the escort police.

At the time of the first gold discoveries, the aborigines in some of the gold-producing areas were extremely troublesome and in the years before the police took charge of the gold escorts, there were numerous attacks with some prospectors and troopers losing their lives.

When the first goldfields opened up, most of the terrain encountered was difficult to traverse and packhorses were used rather than wheeled conveyances. Each horse carried up to 1,200 ounces of gold and was led by one constable. In front were two men with fully loaded guns at the ready, followed at the rear by another armed constable. Also, a number of native troopers were usually employed to lead the extra packhorses which carried blankets, cooking utensils, tents and so on as the trip usually took many days.

As the escort police and horses were not employed solely for gold escort work, this operation took too many police away from the district and in one instance, when 16,000 ounces was conveyed from Georgetown to Croydon, it left one station closed and five other smaller stations with only one or two men on duty. The trip took 22 days and involved an enormous escort squad of 15 police, eight native troopers and 65 horses.

The gold escort about to depart Georgetown, c.1900

Another worry for the Commissioner was the need to procure and keep horses. Each horse had to be kept in top condition for such duties and a lot of them simply couldn’t last the distance. In times of drought, when hay and corn was more expensive, it had to be brought in from larger towns and the cost to the Government was considerable.

In 1870 it was announced by the Commissioner that gold escort vans would be built. This would not only reduce the number of police needed to escort the gold, but would also decrease the number of horses needed, even though four horses were used to pull the coach which could carry up to one ton.

Following is an extract from the 1876 Police Manual that outlines the rules by which gold was to be escorted between the goldfields and the banks.

1 – On the regular lines of road, or on other lines where the amount of gold or treasure is large, the escort will be composed of one officer, one sergeant, and four constables.

2 – One mounted constable will form the advance guard, riding from 100 to 150 yards in front of the conveyance, according to the nature of the country through which the treasure is in transit. One mounted constable will march on the right, and another on the left flank, keeping as nearly as possible parallel with the conveyance, and at such a distance from it, not exceeding 100 yards, as the nature of the country will permit. The other constable will follow in rear, at about the same distance behind the conveyance as the one in front is before, all keeping constantly in view of the officer in charge.

3 – The sergeant will march immediately behind the conveyance, except when ordered by the officer to see that the men are performing their duty properly, under which circumstances the officer will take the sergeant’s place, so that at all times during the march, either the officer or the sergeant may be immediately behind the conveyance.

Gold escort waiting to load seven boxes of bullion at Croydon, c.1905

Depending on the cargo carried (gold, coins or notes) the escort fees varied. Sometimes escort fees would rise if it was a particularly dangerous journey and more men were required, or if a ‘Special Consignment’ was carried. In 1894 the miners on the Georgetown goldfield, angered by the amount of money the Government was skimming off the top, asked for the fee to be reduced from sixpence to fourpence per ounce. In one instance the Government received £184 in fees for the carriage of gold from Georgetown to Croyden but only incurred an actual cost to them of £30.

The Government were raking it in as there were monthly escorts on the Gympie- Maryborough run, the Gilbert and Cape

River goldfields to Townsville run, and the run from Clermont to Rockhampton. But the danger of robbery by bushrangers or attack by aborigines was always present and by 1889 the cost of maintaining the gold escort service had become such a serious issue that it was decided public coaches could do the job just as well.

Cobb & Co. coaches were used with the minimum number of men employed to guard the gold. Inspectors were also removed from gold escort duties. Later, consignments of gold and valuables were carried by train as the railways opened up. Usually only one constable was used in conjunction with railway employees to escort pay boxes to the mines and to escort gold and valuables out.

MURDERS OF POWER AND CAHILL

Seated L to R: Sergeant Julian, Constable Cahill, Constable Power and Gold Commissioner Griffin. The two Native Mounted Police (rear) are not named. (Supplied by Queensland Police Museum)

In November, 1867, troopers John Francis Power, 25, and Patrick William Cahill, 27, were given the responsibility of escorting £4,000 in cash and bullion from Rockhampton to Clermont on horseback.

Rockhampton’s Gold Commissioner at the time, 35-year-old Thomas John Griffin, offered to join the escort on the pretext of the troopers’ inexperience but it was later discovered his real plan was to ride as far as the Mackenzie River, stage a bushranger robbery and steal the cash and bullion for himself.

Griffin owed £252 to six Chinese diggers who had entrusted him with their gold for safekeeping. Griffin subsequently gambled this away. The Chinese men made repeated demands for the return of their gold or its value but Griffin was unable to pay the debt, became increasingly desperate and probably around this time, in August 1867, came up with the idea of robbing the gold escort.

The day before the murders, on November 5, 1867, the three men arrived at the Mackenzie River crossing and set up camp close to where the Bedford Weir sits today. Throughout the day, the trio reportedly frequented a nearby bush pub and Griffin took the opportunity to drug the drinks of the two police officers.

Later that night, Griffin reportedly shot the two men dead and rode back to Rockhampton, burying the money and gold along the way. After Griffin had arrived back in Rockhampton, news broke that Cahill and Power had been discovered dead near where they had camped on the Mackenzie River near Bedford’s hotel, and the money that they had been escorting to Clermont was missing.

A party, including Griffin, was assembled to travel to the scene to investigate the deaths which were initially believed to have been a result of poisoning, after the discovery of two dead pigs near the scene. However, after a post-mortem examination by Dr David Salmond, it was discovered the two troopers had both been shot in the head. No evidence of poison was found, but Dr Salmond expressed an initial view that the two men had been affected by a narcotic of some type and were shot while in a “state of stupor” from its affects.

Griffin was arrested at the scene at approximately 10am on 11th November, 1867, following the exhumation of the two bodies. It was alleged Griffin did “feloniously, wilfully, and with malice aforethought, kill and murder Patrick Cahill and John Power.” His trial started on 16th March, 1868. On 24th March the jury disagreed with Griffin’s plea of “not guilty” and the judge sentenced him to be hanged at the Rockhampton Gaol on 1st June, 1868.

In a bizarre turn of events, more than a week after he was buried, Griffin’s grave was dug up and his head was cut off and stolen.

Rockhampton journalist and historian, J. T. S. Bird, claimed that the main culprit was local Rockhampton doctor, William Callaghan, who took the head away and buried it in a friend’s garden before collecting it. Bird claimed the skull was in the doctor’s local surgery until his death in 1912. There have since been unsubstantiated reports that the skull now sits on a shelf an upper class private residence in Rockhampton.

Research reaps rewards in a Queensland ghost town

By Chris D

The author’s finds at the site

I’ve been detecting for coins and relics for almost 10 years now, and while my enthusiasm for the hobby has waxed and waned over the years, the underlying passion for unearthing the next bit of treasure has never left me. Initially my detecting was centred on local areas around Brisbane which is where I live. No park or reserve was safe from my trusty Teknetics Omega 8000 and, as with most of us, the hobby soon became an addiction. At some stage I upgraded to a Minelab Explorer II which I nicknamed the ‘Silver Slayer’ and now run with a Minelab Equinox 800 which is proving to be the most versatile and ergonomically friendly machine I’ve ever used. Somewhere along the way, finding predecimal coins in local parks became less of a challenge and the history behind the finds started to take on more importance.

The online history hub, Trove, became my new best friend and I started to assemble a range of handy research tools. Suddenly the detective work involved in finding a site became more important than what I actually found. The Eureka moment of unearthing a coin or relic that ‘proved’ a site after months of painstaking research, became my new addiction.

Here in Queensland we’re not as lucky as you buggers down south as the State was only officially formed in 1859, so the age of our sites don’t compare with the really early Australian settlements. Once the restrictions of the penal colony were lifted, a large number of towns sprang up around the old coach routes and then later along the railway lines that linked the expanse that is Queensland. Some of these places survived and grew into the towns we know today, but many, many others, for a variety of reasons, thrived and then died out and were lost to the bush. My driving passion evolved into searching for these lonely, long-forgotten locations and to hopefully uncover some of the secrets of their past.

Some 2,300,000 1914 KGV florins were minted and in Very Good condition they fetch around $16

The 1914 King George V florin as it came to light. At the time it was lost, the drums of World War I were beating

Town B was one of these locations. My research indicated it was a bush settlement in the 1890s with a church, a pub and some shops but it only really thrived from the turn of the century into the 1930s. There was nothing very special about the town itself but what stood out was that they had a very enthusiastic cricket team that played ‘away’ games all around the local area and hosted ‘home’ games at their very own recreation reserve. Trove was full of articles about the town hall that adjoined the reserve, which also had tennis courts and an active tennis club. Piecing together a multitude of information gave me a pretty good general idea of the location and Google Earth did the rest.

The author’s best find was this 1915 penny of which only 930,000 were minted. More than 100 years later, they are fairly scarce. As it marks the year Australians went ashore at Gallipoli, it has historical significance

Eventually it was time to get boots on the ground and when I arrived on site, it was very gratifying to see the remnants of the old tennis court enclosure still standing. I was keen to find the site of the hall, figuring the majority of coins and relics would be in this area. An interesting article in Trove indicated that at one time there was a prize for any batsman who could hit a six over the hall. I knew where the cricket pitch was, so, thinking logically, I looked for any flat ground within a well struck ‘six’ of the wicket and came up with an area near the tennis courts, which, on reflection, made perfect sense.

It didn’t take long to get set up and start swinging. I’m sure everyone can relate to the excitement of detecting a new site, and I actually stopped and took a few moments to enjoy the anticipation of what was hopefully to come. The first coin out of the ground was a beautiful 1903 King Edward VII penny which retained that lovely deep green patina that most of the early British coins seem to have. I was pretty happy to find a coin that reflected the earliest use of the site and now had great expectations for a successful day detecting. For the next few hours I just wandered about as I was planning to return the following week with a mate for a more thorough gridding of the site.

A nice old 1917M (Melbourne Mint) shilling saw the light of day for the first time in a long time, quickly followed by an equally impressive 1920M version. An old brooch, a few pennies and a more modern 1953 Florin came up with the usual rubbish found in these types of sites. Just as I was about to call if quits for the morning, a beautiful high tone stopped me in my tracks. The soil here was very sandy and the coins were coming out in great condition, so I had high hopes this was going to be something special, and I wasn’t disappointed – a lovely 1914 King George V florin that looked like it must have been pretty new when it was dropped. I had only just been reading on the Australian Metal Detecting & Relic Hunting (AMDRH) forum that several members had recently found one and I was hoping their luck might have rubbed off on me. It’s amazing how often, when you visualise something, it actually comes to pass!

The author managed to find an old image of the local cricket team

While I was researching the town I came across an old black and white photograph of the local cricket team. Sitting back looking at the beautiful coin that had just come to light, I wondered if the coin had been lost when one of those ghosts from the past flipped it to see who batted first? Impossible to tell of course, but it’s nice to imagine all the same. These tangible links between the past and the present are what makes the long hours or research worthwhile, and it really is a surreal feeling to handle a coin or relic that was last touched more than a hundred years ago. Hot, sweaty and mildly dehydrated from the heat, I got back in the car feeling well pleased with the morning. I returned the following week with my mate Gary to give the site a more thorough going over. One of the great benefits of this hobby is meeting like-minded people and sharing the excitement of the hunt. Gary and I had met through contact on the AMDRH forum and this was our first combined effort, and one that was eagerly anticipated. It was a typically hot and humid Queensland day and we soon had sweat dripping from our brows. The undergrowth was very thick in a lot of places and prevented any dedicated gridding, however the finds started showing up on a regular basis and kept us both busy for several hours.

It’s been a long time since the last game of tennis was played on these courts but remnants like these are the things you need to keep an eye out for as they are markers of where people gathered

Along with a nice shilling and other bits and pieces, Gary also found the brass top from a 1930s cricket stump which, to my mind, was the find of the day as it tied in directly with the past use of the site. My best for the day was a 1915H (Heaton Mint) penny in pretty good condition – not a rare coin but a harder one to get. As previously mentioned, the soil here was a very sandy type of loam and very kind to the coins with most pennies coming out retaining that lovely green patina. Sitting back enjoying a cold drink and some delicious homemade biscuits Gary’s wife had thoughtfully provided, we couldn’t help but reflect on the tenacity and endurance of the early pioneers who carved out a life in what was once a very isolated location. There really is a deep sense of satisfaction in rescuing these little bits of history from the earth.

Treasure in the Shallows

If you enjoy digging up coins, jewellery, or even gold on dry land, it’s time you thought about getting some gold from shallow water. Sure, there are a lot of things lost on dry land or the beach, but the majority of valuable items are lost in the water and are therefore inaccessible to land-oriented detectors simply because electronics and water don’t mix. But don’t despair.

These days there are numerous affordable underwater detectors readily available from leading manufacturers such as Garrett, Minelab, Nokta and Fisher along with those from lesser-known reputable makers. And of course there are those being turned out by rip-off factories in Guangzhou, China. Avoid these at all costs. Shallow-water treasure hunters have a lot going for them because of the laws of physics.

Heat expands, cold contracts. It’s one of those immutable natural laws. The human body is designed to function on dry land and works best at a temperature of 37 degrees Celsius or 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. When the body enters the water it loses heat 24 times faster than on land. Any scuba diving manual will tell you this. As the body cools, the extremities shrink, fingers included.

That ring that was once a good fit now becomes quite loose as this shrinkage occurs. The body’s natural oils in combination with saltwater makes a great lubricant causing rings to slip off fingers. Unless you happen to have a detector with you at the time, there’s little chance of locating and getting the ring back.

Why? Well, gold has a specific gravity (SG) of 19.2, which in layman’s terms means it is a heavy element, much heavier than sand which has an SG of about 2.5. Because sand is comprised of particles, the ring, being heavier, will bury itself in a very short space of time making recovery almost impossible unless, of course, you have an underwater detector on hand.

People are vain and like to wear jewellery; it’s fashionable and trendy. Women and men both wear wedding rings. The woman might also wear engagement or eternity rings, both of which may contain precious gemstones.

Any treasure hunter would be envious of a collection of gold, platinum and silver rings such as this, especially the rings containing diamonds and other precious gems

While these gemstones by themselves will not elicit a response from the metal detector, the detector will pick up the surrounding metal, which could be gold, silver or platinum.

Next time you go to the beach, have a good look at the hands of swimmers and see how many people are wearing rings and entering the water with them. You’d be surprised. For some reason people just don’t take them off.

Mother Nature is now working on your side because a percentage of those people are going to lose some of their jewellery.

The variety of items found in the water boggles the mind. You can understand rings, watches, charm bracelets, bangles, gold and silver chains, pendants, medallions and coins, but reading glasses and sunglasses, hearing aids, car keys and mobile phones – seriously!

Once you decide to take up shallow water detecting as a hobby, in addition to your detector you will need to make or buy a special recovery scoop and also construct a floating sieve or screen out of an old inner tube (if you can find one in this day of tubeless tyres) and a suitable piece of wire mesh.

Bondi Beach

People have been frequenting beaches in Australia for at least 120 years and they just keep getting more and more crowded. Above we have Sydney’s Bondi on a hot summer’s day.

Dameisha beach

Seems quite crowded until you compare it with Dameisha beach near the Chinese city of Shenzhen. The mind boggles at what swimmers here would lose on a hot day

I use a motor cycle tube attached to a piece of 10cm interwoven mesh. Aviary wire has a tendency to come apart at the solder joints and if you have a very sensitive detector, you could find yourself trying to recover tiny bits of solder that have come away from the sieve.

Almost anyone can get into the water and start winning some gold. All it takes is the desire to succeed and a good dose of patience because at times you can swing that detector back and forth for quite a while without hitting a target.

Because there is also less junk in the water than on the beach, it’s safe to say that most targets will be good ones. There’s nothing quite like looking into the sieve and seeing a nice glint of yellow.

Almost every beach has what is known as a near-shore channel and an off-shore channel. Tidal movements scour these channels and at certain times, rings and other valuables which have been lost, maybe years ago, come within reach of the detector.

I say years ago because it is not unusual to find Victorian-era artefacts in the water. And many of those objects, lost years ago, are still waiting for someone to recover them.

The sea is our last frontier; it’s almost virgin territory to today’s detector operator. In Australia there are thousands of kilometres of coastline, thousands of places where people have swum, and the older the area, the more chance you have of finding something unique, unusual or interesting.

During the late 1970s, when metal detectors first started to make their presence felt here, a new gold rush occurred with people visiting the goldfields in the hope of finding nuggets the old timers missed. Now the gold rush is on in the water because there happens to be tonnes of it waiting to be recovered. With the high cost of fuel today, it’s more economical to drive to the beach than to head to the goldfields in the hope that you might find a speck or two.

Sure, there were plenty of people who were lucky enough to find good gold in the early days but those days are long gone. The majority of the big stuff was cleaned up years ago and traded for a new swimming pool, car or even house. And the Mines Department doesn’t replace the gold nuggets out of the funds it gets from your taxes. On the other hand, my 100-year-old bank is open 24 hours a day. I can go down there most times and with a little work and effort, make a withdrawal or two.

Davey Jones Bank doesn’t worry about paperwork either. Just a little effort and some research into tidal movements, channels, longshore drift and tide times and you could be making those withdrawals too.

There are certain things you will need first up apart from those already mentioned. For starters, you’ll need either a good pair of waist waders or a wetsuit. I prefer a wetsuit because a good 7mm suit will keep you nice and warm and is more streamlined in the water. Waders are all right but should a wave come along or you walk into deep water, they will fill up and you could be in trouble. A good wetsuit should last several years of continuous use so it’s a much better investment.

You’ll also need a sturdy pair of sneakers or wetsuit boots. You often dig up broken glass and unless you have some protection, you could end up with cut feet. Some kind of bag to put your goodies is a must along with another bag to put your rubbish in. If you put your trash in the rubbish bin, you won’t have to dig the same thing up time and again.

People do watch what you’re doing and will frown upon an individual throwing the junk back into the water. Be a good treasure hunter and do the right thing; if you dig it up, dispose of it in the bin where it belongs.

The best times to work are two hours before and two hours after low tide. This allows you to get into the channels where a lot of valuables accumulate.

I prefer to grid a channel by going back and forth across it. Depending on the detector you are using, this could mean having to continually retune as you go.

Other treasure hunters might prefer to search parallel to the beach detecting for perhaps 20 metres and then coming back. If you work it this way, remember to go to the deepest section first as you can always detect the shallower parts as the tide comes in.

Once a target has been located, pinpoint it by using a north-south, east-west crisscrossing method. The target is directly below the strongest signal. Should the target be too big, or near the surface, try lifting the coil to locate the exact target centre. Once located, place your foot behind the coil, remove the coil and use the digging tool to extract the target.

In the USA some shallow water treasure hunters make a handsome living out of what they detect

Here’s where the floating sieve comes in handy because the sand will go through the sieve leaving the target there for you to retrieve. It’s best to supervise this action because if you have a chain, it could easily slip through the mesh so it pays to keep an eye on things. Sometimes you’ll get targets that don’t show up in the sieve. If this happens it was more than likely metal trash such as a small nail or rivet.

But it would be a serious mistake to assume that any beach has been cleaned out. Valuables have been accumulating at any popular beach for more than 120 years and very few people have taken up this hobby and started to recover them. The sea bed can also change dramatically overnight. For instance, one day you’ll search for hours and get nothing, then, overnight, something happens and the next day you’ll have targets galore to pick up.

The best time to search is after a hot, sunny day. Go to the beach during the day and look for the area in the channels where most people are swimming. Go back during the evening, when everyone’s left the beach, and search these areas – you’ll be surprised at the amount of valuables you find.

There’s nothing to stop you working at night either. All you need is a good waterproof or underwater torch. Tie it to your sieve so you don’t have to worry about as carrying it. Just drag it behind you and use it only when you have to. The sea is like a giant Christmas pudding, the valuables being the fruit, the sand being the dough. It’s in a constant state of movement owing to tidal action. Hit the channels on the right day and at the right time and Davey Jones will open up his locker to you for a short while. It won’t last forever so spend as much time as you can in there and get what you can, while you can. The next time you detect the same area I guarantee it won’t be the same.

However, if you’re searching a lake or river bed, it’s a different ballgame because you have no tides to contend with and the object remains where it was dropped. There must be hundreds of old swimming holes around and with a little research it wouldn’t be too difficult to locate them.

A lot of shallow water metal detecting is done in the USA in rivers and lakes and some of the professional treasure hunters there have been known to pick up close to 100 rings in a day from these places.

Precious metals are hallmarked in one way or another and can easily be recognised from plated objects. For example, sterling silver is marked 925, while Britannia Silver, which is used on special occasions, is marked 958. With regards gold, 9ct is marked as 375; 14ct as 585; 18ct as 750; and 22ct as 916. Should you be lucky enough to get an item with 950 on it, you’ve hit the jackpot and got something made out of platinum, which is worth far more than gold.

On a lot of British jewellery there are other hallmarks which denote the mint in which the gold was assayed and a letter which tells you the year of manufacture, enabling you to date your finds. The year was put on for tax reasons. Several books are available on hallmarks and it pays to have one in your library because you could find a valuable antique without knowing it. Antique dealers love to get items for less than their real value so don’t let them profit from your ignorance. Do your homework.

Anyone wearing a wetsuit will find that the extra buoyancy caused by the neoprene rubber will mean they have to start wearing a weight belt with about 10 kilos of lead on it. Even with the extra weight, digging in deep water can cause a few problems especially on deep targets.

Detecting in shallow water is like looking for a needle in a haystack. One must listen carefully to the signals given off by the detector and learn how to interpret them. A good operator, after a short time, will be able to tell the size of the object, be it big or small, but there’s no way of knowing what the target is until you dig it up and it’s in your sieve. Stainless steel digging tools are the best for several reasons. They are light in weight, they cut through the sand faster than mild steel, and they are stronger. On the other side of the coin, stainless steel is more expensive than mild steel and harder to drill and work.

Water causes a lot of drag, especially when the tide’s running. Don’t fight the drag, instead, try to work with it. That drag is good in many ways because it slows down your search meaning you become more methodical. Anyone trying to work too fast in water is not only missing good targets but also putting undue strain on his/ her equipment and also tiring themselves out a lot faster.

Essential gear for a shallow water treasure hunter is a floating sieve and a wetsuit.

Should you arrive at a beach and find a lot of holes already there, don’t worry, there are still plenty of targets that were missed. Check out the holes as you’d be surprised what other operators leave behind. Interest in shallow water metal detecting in Australia is on the increase mainly because of the huge amount of valuables being recovered by those who have already taken the plunge and invested in an underwater metal detector.

I say invested because underwater detecting can be a highly profitable hobby. Many years ago I was told about one bloke who went out and found a four or five ounce gold bracelet containing 18 diamonds. It was valued at more than $8,000 in today’s currency. Not only that but the same guy recovered a diamond ring, with one of the diamonds topping one carat.

If you can get your hands on it, read the book Diamonds in the Surf. It’s only a cheap paperback and Amazon has copies. To help you understand more about the sea, Coasts: An Introduction to Coastal Geomorphology by Eric Bird, is full of useful information.

Here’s something to think about. Say for example, over the course of one year, one ring was lost on a beach per week. That’s 52 rings a year. Yes, I know people aren’t swimming there in winter but it’s an average we’re talking about. Swimming became very popular at the turn of the last century so we have 120 years in which items have been lost. That one beach could have as many as 6,240 rings in it.

Given the average weight of a gold wedding band is between three and four grams, this means there could be up to 24,960 grams of gold buried in the sand on that one beach, or, if you prefer, 802.48 ounces. There are more than 24 popular swimming beaches in Port Phillip Bay alone, so in theory there should be about 19,259 ounces of gold in the bay. And that’s just from gold rings!

This figure is probably conservative because on any hot summer’s day, thousands of people flock to the beach; some are so crowded you can barely move. How many rings are lost in one hot day, no-one really knows but it’s far more than one.

People do lose other things too, such as watches, chains, pendants, coins, bangles, bracelets. So the amount of jewellery in Port Phillip Bay alone would not be a matter of ounces but tonnes. During a trip to one of these beaches with two other underwater hunters, one guy I know bagged four rings, all gold, with a total weight of 39.5 grams. And it probably didn’t make a dent in the amount of gold in that area because it’s constantly being replaced by careless swimmers. Maybe it’s time you opened an account with the Davey Jones Bank.

Come on, what are you waiting for, sure there’s plenty of stuff on the beach proper and along the water’s edge but there’s heaps more just a few metres offshore.

Karratha Gold

Karratha is the commercial hub of a thriving and diverse primary resource industry, located in the heart of the Pilbara some 1,500km north of Perth, Western Australia. During the past decade, investment and major development has transformed the once sleepy outback town to the logistic and commercial capital of the north-west. Karratha is a town full of energy and life, which runs every minute of the day.

Karratha also holds a few secrets. Underneath all the supercharged economic activity is a little-publicised pursuit that only the locals and people-in-the-know are keen to involve themselves in – the hunt for gold.

Reports of gold finds in the region date back to the mid-1870s but for one reason or another, they attracted little attention at the time. As with the early discoveries, gold finds by electronic prospectors were largely kept a secret. The area was not all that well known for its alluvial gold, so local prospectors were generally free to carry on with their activities without much outside interference.

Since the discovery of gold 13 kilometres outside of Karratha in 2008, the town is once again in the spotlight. Unfortunately for hobbyists, there is very little information available on gold localities in the area and not surprisingly, locals are reluctant to share their secrets. As more and more people try their hand at gold prospecting, finding suitable alluvial ground is becoming increasingly more difficult. So where does someone start?

Prospecting the Murchison author, Paul von Zorich, has just released his latest book, Karratha Gold listing all the well-known, as well as some not-so-well-known, alluvial patches around the Karratha–Roebourne region. This, however, is not just another map book. It is the culmination of two seasons of research and field work. The author’s purpose was to deliver concise, accurate and up-to-date information on the gold localities in the region.

Garnets & Flies At Fullarton River

In January 1861, the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition through central Australia reached a creek that Burke named Cloncurry, after his aunt, Lady Elizabeth Cloncurry of County Galway. I very much doubt the good lady even knew where it was let alone visited the place but if she was alive today she might have wished Burke had pegged a mineral claim for her instead of just naming it after her.

Cattle and mining have contributed to the economy of Cloncurry for more than a hundred years but it has been mineral exploration that has brought to light the numerous gemstone localities we enjoy visiting today The Cloncurry area covers all of my favourite gemstones, as I mainly like hard crystals, and my favourite colours, in order, are purple, red, black and yellow. I had already been down to Kuridala and got a little purple amethyst (although a little was disappointing), so red coming next meant garnet and there was no better place to hunt them than at Fullarton River.

Cloncurry in October has always guaranteed us hot weather somewhere around the 40-degree mark, and this trip was no exception. As we travel north each year we acclimatise as we go and 40-degrees in Cloncurry is far better than 10 degrees, windy and raining, in Melbourne.

The garnet site is on Maronan Station and one of the main things the station owners insist on is no travelling on the station roads in wet weather.

We don’t bother with TV while we’re travelling, so we don’t get any weather reports and while I was filling up with fuel the day before our planned trip, I asked the garage attendant whether there was any chance of rain the next day. He gave me a look that said ‘You must be an idiot’, before answering me with, “If you run into some bring it back with you."

My First Gold Ring

Finally a ring of some worth but I must admit I did cheat. A guy I know asked me if I could look for his wedding band that he’d lost approximately 14 years ago while out fishing in waist-deep water. He showed me the spot and even though I figured my chances were none and Buckley’s, the following morning, armed with my trusty Sovereign GT and a very low tide, I gave it a go. Tuning the detector on the beach I got a signal and out popped an 1881 English threepence. Ok, so that was cool and a good way to start the hunt.

The target area was on a low, craggy reef that ran for a 100 metres or more out to sea so I detected my way towards it and a couple of pieces of junk and three sinkers later I was in the target zone. I quickly got a signal down near a sizeable crack in the reef and after a bit of digging and shifting of rocks, lo and behold there it was! Absolutely amazing. I really hadn’t held out much promise of finding it after such a long time, particularly with all the rough seas that you can get along this stretch of coast, but gold is heavy and it just stayed put pretty much where he’d lost it.

It was a happy ending all round because I got to find my first gold ring and he got his gold wedding band back after 14 years in the sea.

The Prospectors Who Missed

Since way back in 1864, when explorer Charles Cooke Hunt, threading his way from rock hole to rock hole across parched country, passed within the proverbial hair’s breadth of the spot where Bayley and Ford 28 years later made their discoveries which were to set the mining world agog, there have been many instances in Western Australian mining history of bonanzas that have been passed over by explorers and unlucky prospectors and of fortunes that have been narrowly missed through a variety of circumstances.

Fate has played some strange tricks in the gold-searching game. It is the glorious uncertainty, the fortune that is always thought to be awaiting the next stroke of the pick that has fascinated men throughout the ages, enticing them to brave hardship and death in a search for the elusive metal. What to one man has looked merely a worthless quartz outcrop has to another been a storehouse of wealth, and thousands of boots have trodden ground which later yielded wonderful slugs.

Early in 1894 a party passed within a stone’s throw of the spot, 12 miles south of Coolgardie, which all the world was to know a little later as the Londonderry, without seeing a sign of gold.

It was left to John Mills, Huxley, and their four mates to knock the precious metal from the reef, more than £30,000 being dollied by them within a few weeks. The story is told that Mills, a native of Londonderry, not long over from New South Wales, lay down to have a smoke one evening, a bold outcrop at his feet. Imagine his feelings when he found the outcrop contained gold in abundance. But Mills was not excited. After supper he told his mates he had something to show them, and leaving the camp he returned with his hands full of specimens. They worked day and night getting out the gold by the lost primitive methods, and had about 8,000oz before Coolgardie knew of their discovery.